Enslavement History of the Property

The Thomson family, into whom Thomas Cole married, enslaved people from at least 1790 until 1820. In 1815 the Federal-style Main House that remains today was built by a group that likely included enslaved laborers. Cedar Grove, the historic name of the property, became a substantial working farm of about 110 acres. Ongoing research is being done on our Site to collect and share stories of Cedar Grove’s enslavement history, and the people who labored and worked to make life for Thomas Cole and this household possible.

The following historic documents may contain outdated and offensive terminology. Please read with care.

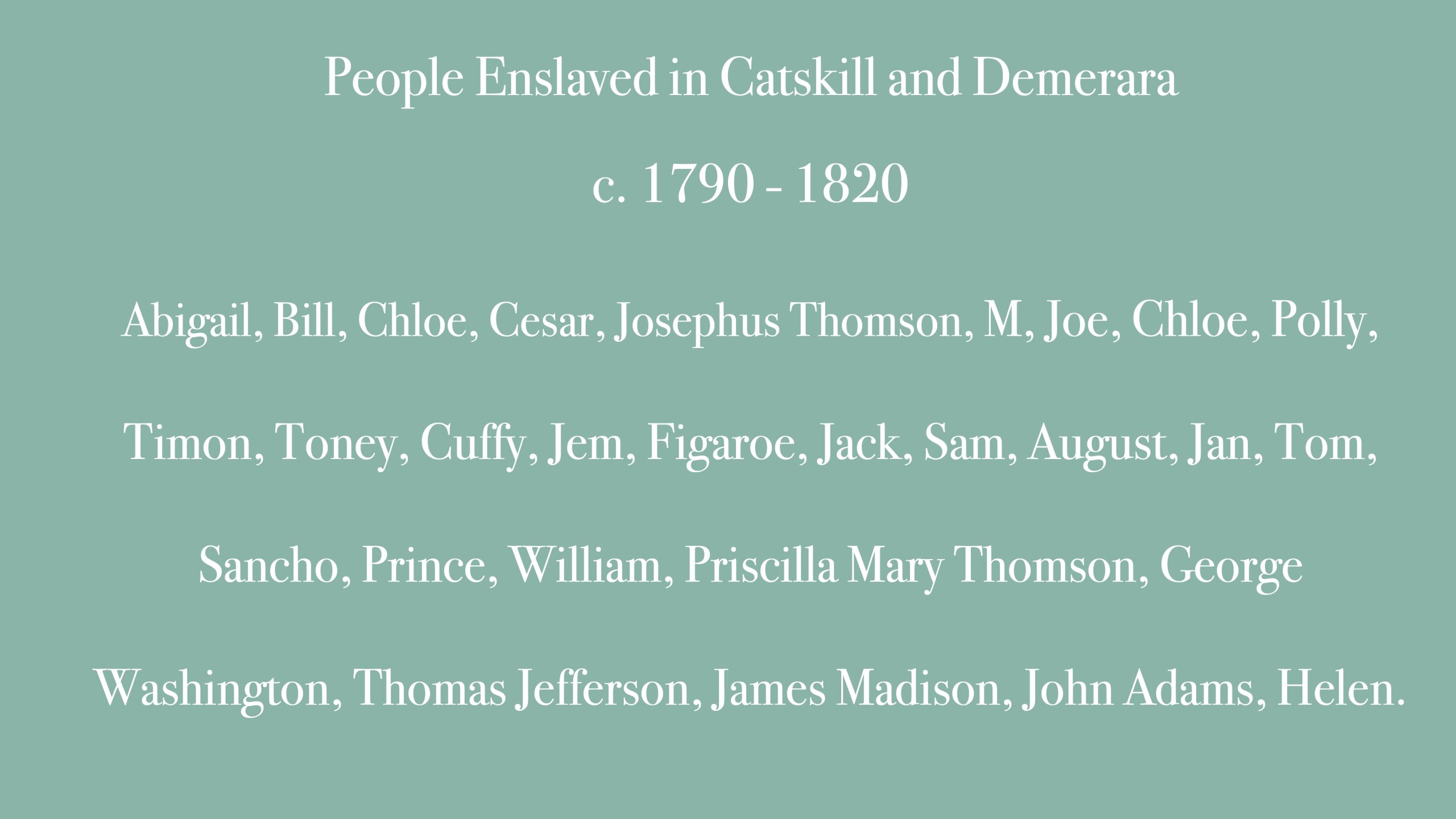

At least 30 individuals were enslaved by the Thomson family in Demerara and Catskill.

Abigail, Bill, Chloe, Josephus Thomson, and Cesar were individuals enslaved here in Catskill. M, Joe, Chloe, Polly, Timon, Toney, Cuffy, Jem, Figaroe, Jack, Sam, August, Jan, Tom, Sancho, Prince, William, Priscilla Mary Thomson, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Adams, and Helen were individuals enslaved in Demerara. Two men, a stone-sawyer and a domestic servant whose names were not recorded, were listed for sale at Thomas Thomson’s Demerara storefront. Countless others were likely enslaved by Thomson in his inherent participation of the triangular market.

The Main House and the TransAtlantic Slave Trade

From 1804-1814, Thomas Thomson, one of the original owners of the Main House and uncle to Maria Bartow Cole who married Thomas Cole, actively participated in the enslavement of people in Demerara in South America (present-day Guyana). There he enslaved people who labored at his Demerara estate, traded profitable goods, and sold household wares at a Plantation storefront. At least 25 people were enslaved by Thomson in the West Indies.

He was in a long-term union with a woman named Priscilla Mary Thomson, a previously enslaved woman who held shop with him. They had five children together named George Washington, James Madison, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Helen. Thomas Thomson returned to New York in 1815 in time for the building of the Main House, leaving Priscilla Mary and their family behind. The money he accrued during the TransAtlantic Slave Trade helped to finance the home.

Slavery and Abolition in Castkill, NY

After failed attempts in 1785 and 1788 to emancipate enslaved people in New York, the New York State Manumission Act of 1799 passed with the final period of emancipation not set until July 4, 1827.

Convening against the institution of slavery and connecting with community was powerful and necessary during such heightened threats to the safety of the Black community. Black Catskill residents accounted for less than 6% of the recorded population in Catskill’s rural community of the 1840s, though many people of color were left out of county and federal records entirely. Errors in record taking and the deliberate mismanagement of demographic statistics in the 19th century makes this a faulty percentage. In reality, Catskill was an important hub for abolitionist activity, with Vigilance Committees forming across the state and in nearby Albany, and Black Catskillians maintaining their own market ventures, celebrations, gardens, and making major contributions to economic developments in the village.

What are manumissions?

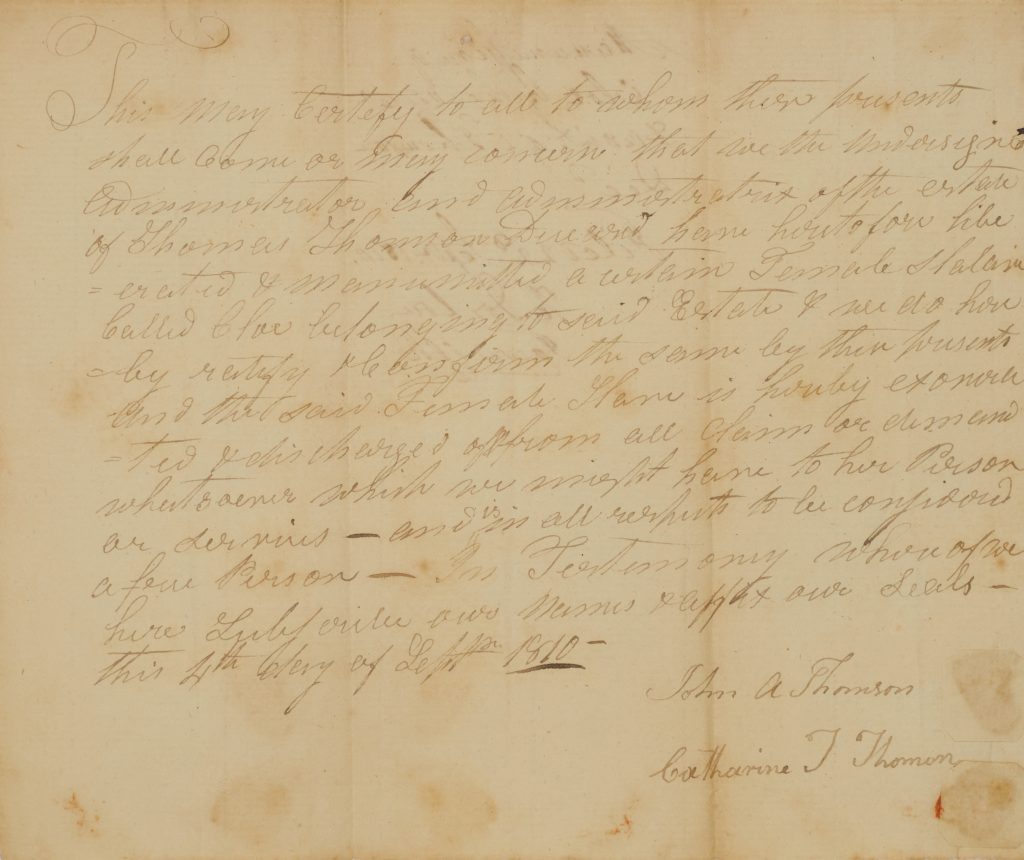

Manumission documents, also called emancipations or certificates of freedom, were documents that made official the act of emancipating or setting an enslaved person free from slavery. A freed Black person would need to file their manumission with a county deeds office to serve as a legal affidavit proving their free status against kidnappers and enslavers. With gradual emancipation, the Thomsons would have kept the a copy of these documents as proof that they freed those they enslaved. We have found four manumission documents in the Thomson family’s papers for a woman named Chloe, a man named Cesar, a man named Bill, and a man named Josephus Thomson. We have little surviving information on these individuals, whose lives went unrecorded by family and historians.

The abolition of slavery in New York State was a long and difficult process. After multiple failed legislations to free enslaved persons in New York, a final period of emancipation was set for July 4, 1827. Though even this did not guarantee freedom for all.

What does it mean when the only record of a life is a manumission document? How do we recall and memorialize the life and labor of these individuals?

Don’t miss this: Chloe, Bill, Josephus, and Cesar’s manumissions are now reproduced on the chair of John Alexander Thomson or “Uncle Sandy” who signed these documents.

Chloe

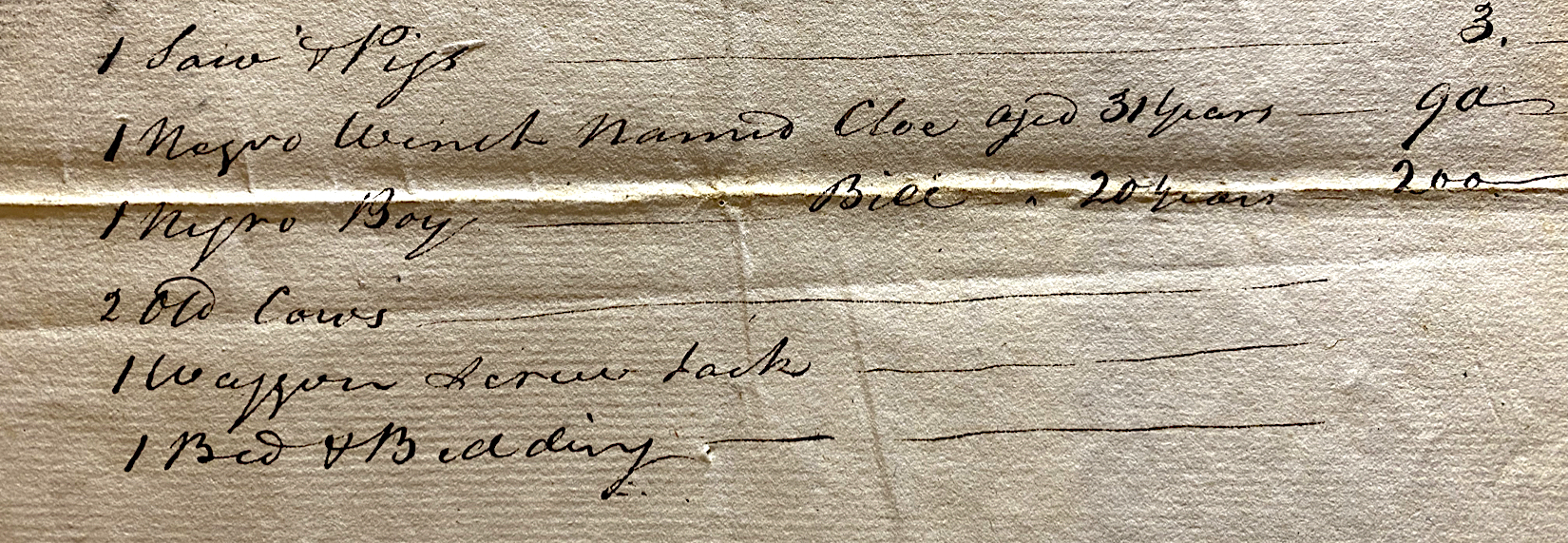

Chloe, born circa 1774, was formerly enslaved by the Thomson family. The names of Chloe and Bill, another person enslaved by the Thomsons, appear at the bottom of a personal inventory following the death of Dr. Thomas Thomson in 1805, father of Thomas, John Alexander, and Catherine Thomson, who were the original owners of the property established in 1815. Chloe and Bill’s names are cushioned between the listings of “2 old sleighs,” a pitchfork, shovels, and “1 old bay mare.” This kind of treatment to their personhood shows how readily and intentionally Dr. Thomson and his estate considered them to be their personal property.

Chloe continued to be enslaved by the Thomsons until 1810, at which point she received her manumission certificate. In an accompanying document which proved her ability to care for herself independently, a crude legal process that ensured John Alexander and Catherine Thomson would no longer be liable for supporting her, she is listed as being under fifty years of age. Five years later, the Main House was built. While it is uncertain whether Chloe continued to work for the family as a newly emancipated person, we wonder how her life may have continued.

What were her joys? Could she practice any hobbies? Could she read or write? Did she enjoy poetry? In 1840, a free, Black woman between 55-99 years of age was recorded as a resident of the household. The 1840 census only recorded the name of the head-of-household and thus her name is presently unidentified. Perhaps Chloe continued to work for the family for several decades longer, perhaps as far as 1840 at age 66. It would be a special circumstance if she worked for the Cole, Bartow, and Thomson family for so long as many Black families in Catskill by then were forming their own households. To read more representational history on the free, Black woman whose name was once known, visit Who Was She?

This May Certify to all to whom these presents shall come or may concern that we the undersigned administrator and administratrix of the estate of Thomas Thomson Deceased have heretofore liberated & manumitted a certain Female [illegible] Called Cloe belonging to said Estate & we do hereby rectify & confirm the same by their presents and that said Female Slave is hereby exonerated & discharged of & from all claim or demand whatsoever which we might have to her person or services – and is in all respects to be considerd a fine Person – In Testimony where of we here subscribe our names & apprix our seals – this 4th day of Septr. 1810 –

John A Thomson

Catherine T Thomson

Bill

Bill was born circa 1785. His name appears on the 1805 inventory following the death of Dr. Thomas Thomson, where he is recorded as being 20 years old.

Whether or not Bill received his manumission from the Thomson family is unclear. It is clear that he continued to labor for the Thomson family in 1806 when in an account book of John Alexander Thomson it lists “1 pr shoes for Blk boy bill.” He continued to be provided with clothing by John Alexander in the following years of 1811, 1812, and 1813. Fabric for Bill was cut and sewn for cloth jackets, shoes, and pants. Through these small lines on receipts to a local tailor, we begin to see a visual image of Bill through the clothing that he wore.

The details of Bill’s life come in fragments of records for individuals who bear similar names. On April 30, 1816, a Bill Thompson appeared in a court document stating his eligibility to vote as a free person in Catskill. He showed up in court and gave proof of his freedom which was satisfactory to Catskill Judge Abeel; this kind of proof was necessary to participate in local elections as a formerly enslaved person.

In James D. Pinckney’s Reminiscences of Catskill: Local Sketches, Bill Thompson is remembered as the Village Sexton of a Catskill cemetery. In other words, he provided the grounds care, likely ringing church bells, digging graves, and tending to the land.

1 Negro Wench named Chloe aged 31 years – 90

1 Negro Boy – Bill – 20 years – 200

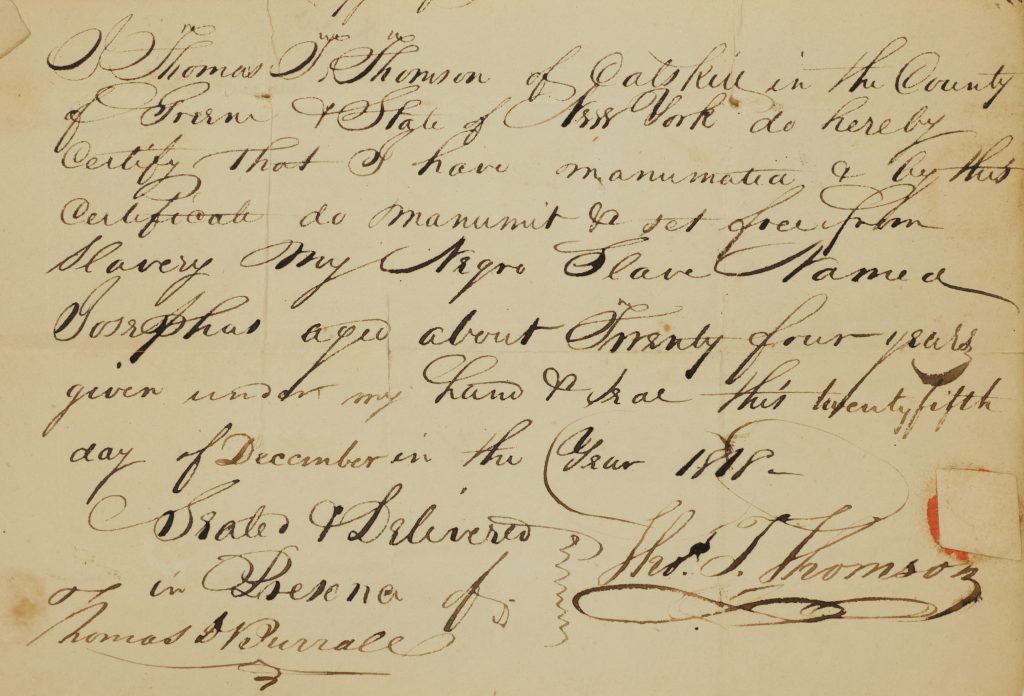

Josephus Thomson

Josephus Thomson was a free, mixed race, and formerly enslaved man who was the primary servant to Thomas Thomson from 1797 to 1818. He was born in New York around 1794 and accompanied Thomas Thomson to Demerara for the length of 10 years, at which time he likely served as his closest confidant, assisting Thomas Thomson in his everyday tasks. On a ship ledger from the Port of Liverpool, Josephus is described as being mixed race, 5ft 7in, having black hair and dark eyes, and his profession marked as a “servant to Mr. Thomson.”

Josephus was born an enslaved person, and at just three years old, he was passed into the ownership of Thomas Thomson, one of the original owners of the estate, from his father Dr. Thomas Thomson.

Josephus Thomson continued to be enslaved by and in service to Thomas Thomson in Catskill in their return from Demerara, caring for Thomas Thomson’s malady, likely syphilis, and attending a local masonic fraternity meeting with him.

He received his manumission from Thomas Thomson in 1818 on December 25, Christmas day. As a newly emancipated individual, Josephus moved to Athens, NY, about an hour’s walk from Catskill, where he became head-of-household at his own property, seeming later to foster a fuller household of other free, Black individuals. Josephus continued to live in Athens for several decades, outliving Thomas Thomson by several years. His path may have crossed directly with Thomas Cole’s, perhaps the two even knew each other. The search for more details on Josephus’ inner and outer life are ongoing.

I Thomas T. Thomson of Catskill in the Country of Greene & State of New York do hereby certify that I have manumatid & by this certificate do manumit & set free from Slavery My Negro Slave Named Josephus aged about twenty four years given under my hand & seal this twenty fifth day of December in the Year 1818 –

Stated & Delivered

in Presence of Thos. T. Thomson

Thomas D BurrallJohn A Thomson

Catherine T Thomson

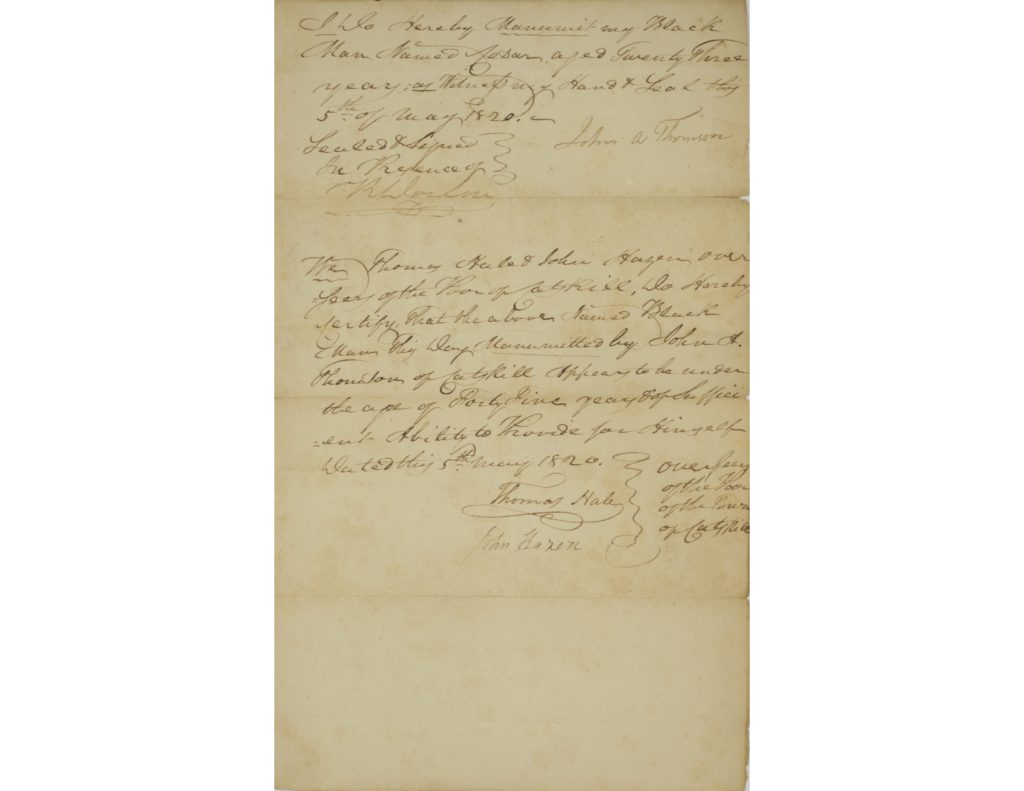

Cesar

Cesar was the last individual to receive his manumission from the Thomsons in 1820. He was probably close in age to Josephus, both of their names appearing on a clothing receipt where they were each cut a pair of pantaloons from a local tailor. Like Bill, Cesar and Josephus were provided with clothing by John A. Thomson who signed the manumission certificates for both men.

In Reminiscences of Catskill it is suggested that Cesar also accompanied Josephus and Thomas Thomson to Demerara. As the last recorded person manumitted by the family, was Cesar’s experience isolating? Did he have opportunities to connect with Josephus and other Black Catskill community members?

I Do Hereby Manumit my Black Man Named Cesar, aged Twenty Three years; as witnessing Hand & Seal this 5th of May 1820.

Sealed & Signed In Presence of R. Dorlow

John A ThomsonWe Thomas Hale & John Hazen overseers of the Poor of Catskill, Do Hereby Certify, that the above Named Black Man this Day manumitted by John A. Thomson of Catskill Appears to be under the age of Forty Five years & of Sufficient Ability to Provide for Himself

Dated this 5th May 1820.Thomas Hale

John Hazen

overseers of the poor of the poor of CatskillJohn A Thomson

Catherine T Thomson

Priscilla Mary Thomson

We are all here looking + wishing to see you every day, and very anxious to here [sic] from you — if we are not to have the pleasure of seeing you soon——your absence Childrens — make things very different to me — in comparison to what they formerly were — I find myself very lonesome.

Priscilla Mary Thomson was a shopkeeper and previously enslaved woman who conducted considerable shop affairs alongside Thomas Thomson in Demerara between the years of 1804-1815 while Thomson was deeply entwined in trading and the enslavement of people during the TransAtlantic Slave Trade.

Priscilla Mary and Thomas Thomson held a common-law relationship for the period of 10 years.

Her colonial affairs and participation in the market culture in Demerara was significant. Priscilla Mary held a managerial position at their estate in Demerara, keeping watch over their household staff who were enslaved women and young boys named Polly, Linda, Eliza, Chloe, and Toney.

Priscilla Mary and Thomas Thomson had five children together named George Washington, James Madison, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Helen. When Thomas Thomson left Demerara never to return again, Priscilla Mary urged him not to forget their children. She exercised great authority when in 1833, she sued the estate of Thomas Thomson for the board, education, and care of their five children from 1804 – 1814. She was awarded approximately a fourth of what she requested, the rest of the money provided covered legal expenses. It was John Alexander Thomson who settled the matters of this lawsuit on behalf of his deceased brother.

“The Plaintiff states and avers it to be true that the said Thomas T. Thomson did between the years 1804 and 1814 beget on the body of her the Plaintiff the five children named respectively Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Washington, John Adams, and Helen as she is ready and willing to attest on Oath.”

Emancipation Laws, New York State

1799 Gradual Abolition Law: New York introduced gradual emancipation of the children of enslaved women born after July 4, 1799. Children were born “free”, but had to perform free labor for their mother’s masters until the age of 25 (for women) and 28 (for men). All those born before July 4, 1799 were enslaved for life.

1817 Final Act of Emancipation: New York legislature marked July 4, 1827 as the date for final emancipation

JULY 4, 1827: Date of final emancipation of enslaved people in New York State (exceptions still applied)

1841: The exceptions to the 1827 abolishment of slavery in NYS are now also legally abolished when the state revoked a law that made non-residents able to hold people enslaved for a period of up to nine months.

Sources

Manumission Certificates, Office of the Greene County Clerk, Manumissions & Indentures, Greene County Records Management.

Mighty Change, Tall Within: Black Identity in the Hudson Valley, ed. Myra B. Young Armstead (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003), 41.

Myra B. Young Armstead, Freedom’s Gardener: James F. Brown, Horticulture, and the Hudson Valley in Antebellum America, (New York and London: New York University Press, 2012).

Thomson Family and Cole Family Papers, Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Catskill, NY.

Thomson Family Papers, New York State Archives, Albany, NY.

US Census Bureau, “1840 Census: Compendium of the Enumeration of the Inhabitants and Statistics of the United States,” Census.gov, February 10, 2023, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1840/1840v3/1840c-02.pdf.

Project Team

Planning Team: Vicente Cayuela, Sofia Thieu D’Amico, Adaeze Dikko, Carrie Feder, Jennifer Greim, Traci Horgen, Elizabeth Jacks, Amanda Malmstrom, Kristen Marchetti, Kate Menconeri, Maura O’Shea, Heather Palmer, Beth Wynne.

Implementation, Design, Production, Conservation: Matt Alexander, Jessica Goon, Paul Harwood, Bob Howard, Geoff Howell Studios, Hudson Valley A/V, Andrés Laracuente, Maeve McCool, Mark Reed, Lopez Restorations, Garry Nack, Peter Noci, Tone Noci, Jude Ray, Zazie Ray-Trapido, Paul Trapido, Adrienne Westmore, Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Rob Wynne.

Advisors: Myra Young Armstead, Debbie Bruno, Elon Cook Lee, Jean Dunbar, Lisa Fox Martin, Sylvia Hasenkopf, Amy Hufnagel, Jonathan Palmer, Warner Shook, Nancy Siegel, Jean-Marc Superville Sovak, Stephanie Sparling Williams.

Audience Research: Michael Barraco, Jacy Barber, Isabelle Bohling, Martha Bradicich, Heather Christensen, Meg DiStefano, Lora Lee Ecobelli, Brooke Krancer, Eric Longo, Gabby Ricciardi, Catherine Sharkey, Mary Beth Soya, Ava Teague, Nancy Winch, Jacquelyn Woods.

This project has been funded in part by National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Telling the Full History Preservation Fund, with support from National Endowment for the Humanities.

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this website do not necessarily represent those of the National Trust or the National Endowment for the Humanities.