Who Was She?: In Search of the History of a Free, Black Woman, Whose Name was Once Known

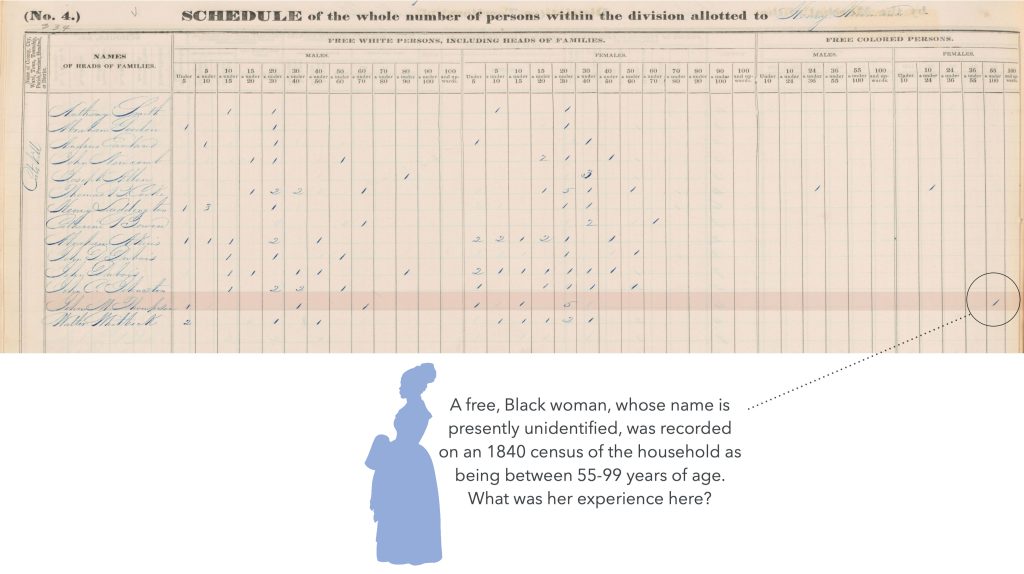

In 1840, the recorded population of the town of Catskill was 5,339 people. Of that total, only 11 Black women, aged 55-99, were recorded on the federal census as “free.”

One of those women lived here.

A free, Black woman whose name went unrecorded was listed on the 1840 census of the household as a resident. Based on her recorded age of 55-99 years and New York State laws, she was very likely born as an enslaved person between 1741 and 1785. We seek to understand the history of her life as it was singular to, absent from, and paralleled the history of Thomas Cole’s idyllic residency in Catskill, NY.

As we come to understand the details of her life through primary source documentation and representational histories of other free and enslaved Black women who lived in the Hudson Valley and greater New York State in the 19th century, we sit with questions of her experiences in the household, her engagement with the local community, and her own individual connections to land, landscape, and labor.

The following historic documents may contain outdated and offensive terminology. Please read with care.

Her Absence From Family Letters

Maria Bartow Cole’s letters to husband Thomas Cole are filled with news of their children, her sisters, her uncle, and visitors. Missing from these is the name or mention of a Black woman who is documented as a free person and resident of the household in 1840. She likely held a pivotal role in maintaining the home, and yet her name was left out.

Indispensable but Unrecorded

The woman cited on the 1840 census was potentially involved in a great many laborious tasks around the house and property. She may have been responsible for household cleaning, caring for the Cole children, or preparing food and drink. Maybe she made preserves from the orchard’s fruit. Perhaps she answered the door when Thomas was expecting an important guest.

Her Experience Outside this House

She may have been going into town for goods and materials. A day out in town involved speaking with shopkeepers and buying household items to accommodate Thomas Cole’s guests and the comforts of the household. The Thomsons owned a number of brick stores in town stocked with pink ribbons, calico fabrics, and crockery. Maybe she was buying gingham for Maria’s sewing, flour for griddle cakes, and packages of tea for the many guests and patrons coming to the house.

This was a moment that may have provided her the opportunity to connect with other Black community members, other women working as domestic servants, and other Black women harnessing their purchasing power as consumers. Many Black women in the Upper Hudson Valley found ways to generate profits and buy their own personal, desired goods by trading self-grown and cultivated herbs, corn, dried apples, beans, and potatoes (Agnew, Mighty Change, Tall Within: Black Identity in the Hudson Valley).

Would she have had any opportunities for leisure? Did she attend church? Thomas Cole was of the Episcopalian faith. Perhaps she attended St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Catskill alongside the Cole family, the Dutch Reformed Church, which was an integrated congregation, or the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Congregation in Coxsackie, est. in 1853. We continue to consider her life through questions of her experiences outside that of her labor.

It seems the more we inquire, the less we know, and the more we open ourselves up to catching glimpses of the Free Black Woman in our contemporary world. For me, this dynamic and even strained relationship with the Free Black Woman is the definition of legacy. It is a legacy that falls apart and pieces itself together again and again; and still we find that her presence is strong and near.

When we regard legacy in this manner, we no longer feel beholden to a version of history that is neat and digestible. Instead, we commit ourselves to exposing and tending to that which is chaotic and unimaginable and everything in between— that which is human.

Being “Free” and Abolitionist Activity

Slavery was legal in New York State until 1827. Regardless, there continued to be holes in the legislation leading up to the abolition of slavery in New York and in the years thereafter.

The Fugitive Slave Law fiercely affected Northern States. In her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs called New York City, just 100 miles south of Catskill, the “city of kidnappers.” Catskill was not without similar activity. Several free persons living in New York were captured and taken to Southern States where slavery was still legal. Living in Catskill as a free, Black woman came with its dangers.

By the 1830s, abolitionist activity was well underway in Catskill to protest these circumstances. Black abolitionists Martin Cross and Robert Jackson were leading conventions and mobilizing here in Catskill. This was a period of inspiration despite such violence.

The free, Black woman living at Cedar Grove may have been able to foster meaningful interactions with other Black community members, organizers, and abolitionists in her Catskill neighborhood over food, market outings, and home-keeping, maybe even through direct interactions happening on this very property.

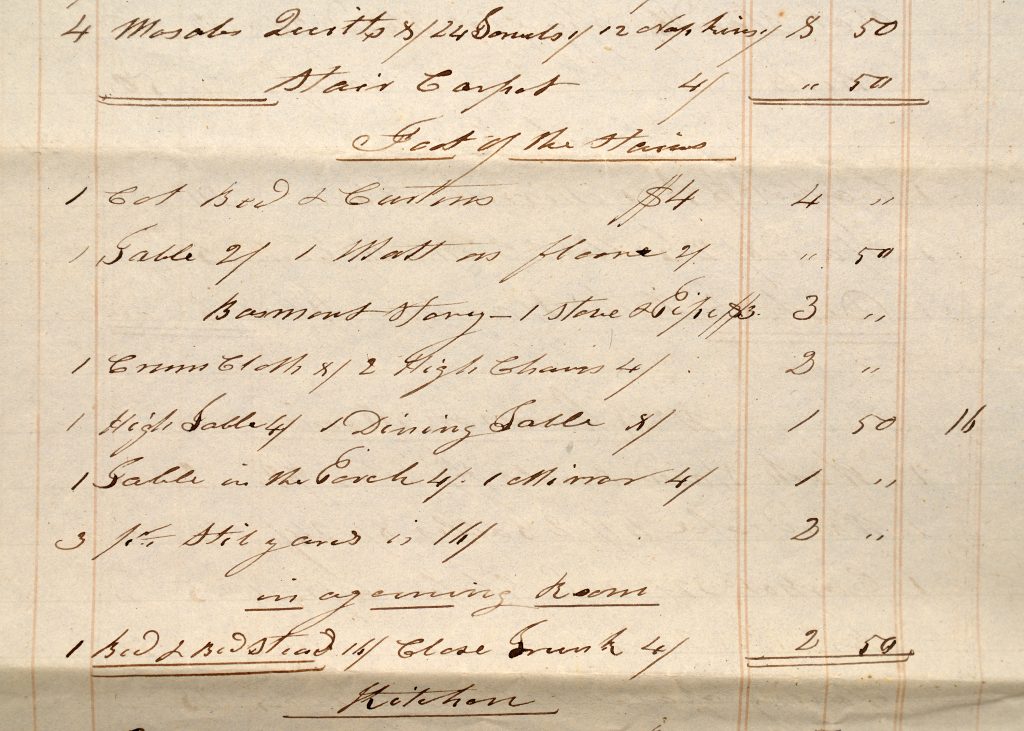

“1 cot bed and curtains; 1 table; 1 mat on the floor.” The imagery is palpable and indeed . . . we have even more questions.

“Foot of the Stairs” and Catskill Community

Alongside other rooms that were inventoried at the time of John A. Thomson’s death, the 1846 Inventory of the Property of John A. Thomson lists a space at the “foot of the stairs.” Only three items appear: 1 cot bed and curtains, 1 table, and 1 mat on the floor. These items are simple and scarce, and indicate that the space at the foot of the stairs was likely a sleeping space for someone who worked in the home. What was that experience like?

For a live-in laborer, this sleeping space was intentionally close by to the work areas and rooms where their household tasks took place. The kitchen was to the right and a milk room was to the left, providing this person little to no separation from work and leisure, and leaving them vulnerable to the demands of the household at all times. Many women of color living and working in white households were vulnerable to predatory and abusive behavior in the antebellum period. And yet, this space might have at times been an access point. With doorways off of the kitchen leading outside to the farm and carriage-path, were there opportunities to maintain a sense of community with the other workers?

In Catskill’s rural population of the 1840s, the recorded Black population figured less than 6%. Her sense of community might have manifested directly on the property through convening with the other working members of the farm and household. Furnishing and historic interiors expert Jean Dunbar has interpreted the basement kitchen as “a place where classes and ages mixed,” based on furnishings that most likely accommodated a dining space for both household workers and family members.

Inventory of the Personal Property of John A. Thomson Deceased, Foot of the Stairs, (Inventory Documenting a Sleeping Space at the Foot of the Stairs), 1846, ink on paper, 16 in. x 13½ in., Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Catskill, NY, Box 7, Folder 8, 1846.3, Photo: Vicente Cayuela

Census Disparities

The 1840 Census of this household which cites a free, Black woman as a resident leaves much to be deciphered. Her figure is a small tick mark out of many illustrating the 11 individuals who resided on the historic property. There were major gaps in recording the age of free, white individuals versus free, Black individuals and enslaved persons, with 5-10 years marking the age range for white people and a range of up to 45 years marking the age for people of color. How then do we identify the true details of her life through falsified records?

From 1800-1840, the individual permitted to speak to the census taker on behalf of the household was limited to a free person over 16 years of age. Recording prioritized the head of household and their direct family. Oftentimes, names were misspelled and ages fluctuated. For the recording of Black individuals, specificity was not a priority, and many people were left out of census records and other federal documents entirely.

The 1850 Census was the first federal census to include the names of individual household members rather than the existing method of only noting the head of household, who was often, but not always, a white, property-owning male. On the 1850 Census, there are women born between 1741-1785 with the last name Thomson or Thompson, as it was commonly spelled with the letter p, whose names offer possibilities in identifying the name of the free, Black woman who was recorded as a member of the historic household.

It is important to note that these women lived out individual lives, and while their histories may be viewed through a shared experience as seen through being free, women of color living in Greene County, they were singular persons with various home and social circumstances.

For more, check out the research of two of our Cole Fellows, Adaeze Dikko and Beth Wynne: Regarding the Free, Black woman documented as a Cedar Grove Resident and Contextual Research on the Unnamed, Free Black Woman and Other Laborers at Cedar Grove.

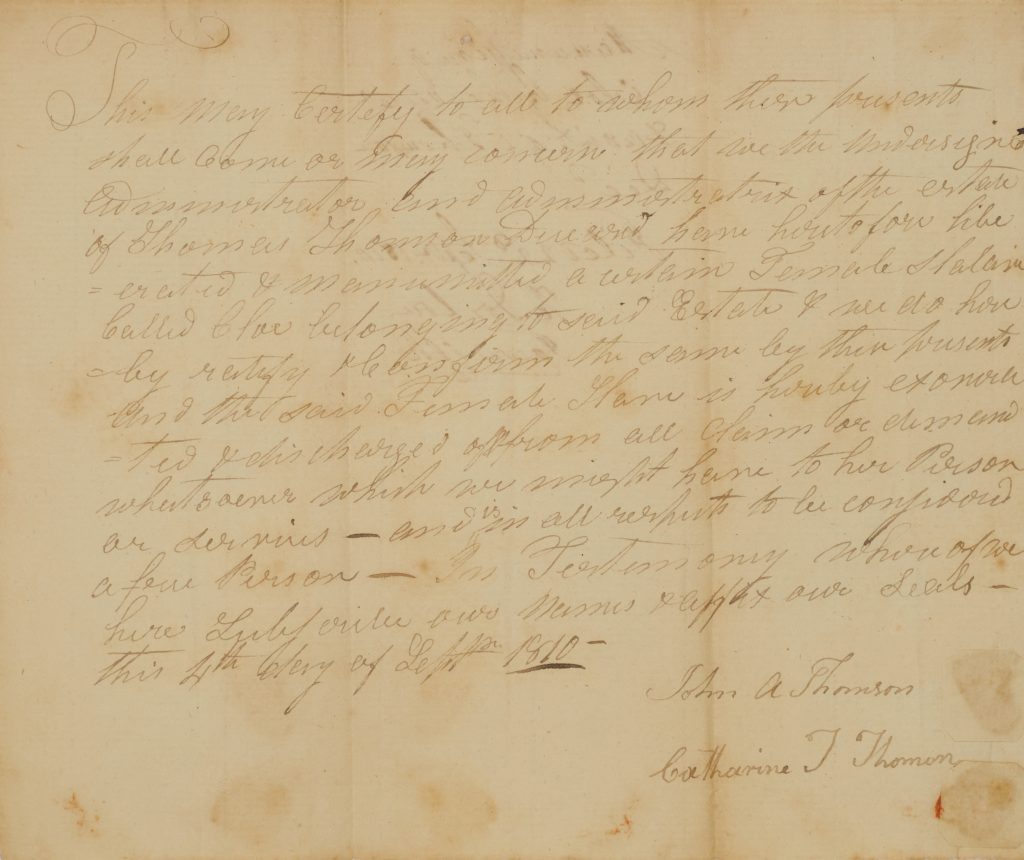

Searching for Her Name: Was She Chloe?

Chloe was a previously enslaved woman who received her manumission from the Thomson family in 1810. Born in 1774, Chloe was recorded as 31 years of age in 1805 on an inventory following the death of Dr. Thomas Thomson, father of John Alexander, Thomas, and Catherine Thomson, original owners of the Catskill estate.

Indeed, Chloe’s age comes closest to the disparaging age range of 55-99 years listed on the 1840 census for a free, Black woman; in 1840, Chloe would have been around 66 years of age.

Perhaps Chloe, who was enslaved by the family for the length of at least 5 years, continued to work for the Thomson, Bartow, and Cole families for an indefinite amount of time as a newly emancipated woman. As a woman who was likely born enslaved, what was her experience in the Hudson Valley before and after receiving her emancipation?

Read more about Chloe and other individuals who were enslaved by the Thomson family here.

This May Certify to all to whom these presents shall come or may concern that we the undersigned administrator and administratrix of the estate of Thomas Thomson Deceased have heretofore liberated & manumitted a certain Female [illegible] Called Cloe belonging to said Estate & we do hereby rectify & confirm the same by their presents and that said Female Slave is hereby exonerated & discharched of & from all claim or demand whatsoever which we might have to her person or services – and is in all respects to be considerd a fine Person – In Testimony where of we here subscribe our names & apprix our seals – this 4th day of Septr. 1810 –

John A Thomson

Catherine T Thomson

Sources

Aileen B. Agnew, “‘Living in a Material World’: African Americans and Economic Identity in Colonial Albany,” in Mighty Change, Tall Within: Black Identity in the Hudson Valley, ed. Myra B. Young Armstead (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003), 41.

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (New York: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2005), 95.

Jean C. Dunbar, Furnishings Plan (Catskill, NY: Thomas Cole National Historic Site, 2011), 129.

Psyche Williams-Forson, “Where Did They Eat? Where Did They Stay?: Interpreting the Material Culture of Black Women’s Domesticity in the Context of the Colored Conventions,” in The Colored Conventions Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century, ed. P. Gabrielle Foreman, Jim Casey, and Sarah Lynn Patterson (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

Project Team

Planning Team: Vicente Cayuela, Sofia Thieu D’Amico, Adaeze Dikko, Carrie Feder, Jennifer Greim, Traci Horgen, Elizabeth Jacks, Amanda Malmstrom, Kristen Marchetti, Kate Menconeri, Maura O’Shea, Heather Palmer, Beth Wynne.

Implementation, Design, Production, Conservation: Matt Alexander, Jessica Goon, Paul Harwood, Bob Howard, Geoff Howell Studios, Hudson Valley A/V, Andrés Laracuente, Maeve McCool, Mark Reed, Lopez Restorations, Garry Nack, Peter Noci, Tone Noci, Jude Ray, Zazie Ray-Trapido, Paul Trapido, Adrienne Westmore, Williamstown Art Conservation Center, Rob Wynne. Special thanks to Historic Deerfield for enabling us to replicate an object from their collection (“field or camp bed,” HD 53.094.2).

Advisors: Myra Young Armstead, Debbie Bruno, Elon Cook Lee, Jean Dunbar, Lisa Fox Martin, Sylvia Hasenkopf, Amy Hufnagel, Jonathan Palmer, Warner Shook, Nancy Siegel, Jean-Marc Superville Sovak, Stephanie Sparling Williams.

Audience Research: Michael Barraco, Jacy Barber, Isabelle Bohling, Martha Bradicich, Heather Christensen, Meg DiStefano, Lora Lee Ecobelli, Brooke Krancer, Eric Longo, Gabby Ricciardi, Catherine Sharkey, Mary Beth Soya, Ava Teague, Nancy Winch, Jacquelyn Woods.

This project has been funded in part by National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Telling the Full History Preservation Fund, with support from National Endowment for the Humanities.

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this website do not necessarily represent those of the National Trust or the National Endowment for the Humanities.