Do you own a Hudson River School painting?

If you own a special work of art, you are part of a long tradition of patrons and collectors that have supported artists and derived great pleasure from their masterworks. Here at the Thomas Cole Historic Site, we receive many inquiries from collectors about a wide range of topics that relate to their paintings; therefore, this section of our website is dedicated to the collector. It attempts to answer some of the most frequently-asked questions, and in the future we plan to provide a forum for sharing information among a community of individuals that share common interests.

For the frequently-asked questions section below, our thanks to Louis Salerno at Questroyal Fine Art for providing the expert advice. We invite you to explore the information and links that are listed below, and enjoy your work of art!

1. How can I confirm that my painting is a nineteenth-century original?

The first thing to do when evaluating your work of art is to make sure it is, in fact, a painting and not a print. Paintings and prints have become so similar with technology that sometimes a professional cannot immediately tell the difference between the two. One way to see if you have a painting is to look for brushstrokes and verify that the composition does not consist of pixilated dots, which can indicate that the art is machine-made. If you believe the painting is on canvas, then you might also check the back to judge the age of the work; a nineteenth-century canvas will typically look dark and quite aged, unless it has been restored. Even with these tricks, your safest bet is to send an image to a trusted dealer or restorer to provide an initial evaluation of the work.

Fig. 1 Prints and paintings can look very similar and it is necessary to look closely. Here, the work on the right is an original painting, whereas the image on the left is a print. Both are by Hudson River School artist Albert Bierstadt. Left: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie, 1869. Chromolithograph, 19 1/8 x 32 3/8 inches, published by Thomas McLean, London. The Collection of The Old Print Shop, New York, NY. Right: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), Indian Encampment. Oil on paper laid down on board, 7 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches, signed lower right. The Collection of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

Fig. 1 Prints and paintings can look very similar and it is necessary to look closely. Here, the work on the right is an original painting, whereas the image on the left is a print. Both are by Hudson River School artist Albert Bierstadt. Left: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie, 1869. Chromolithograph, 19 1/8 x 32 3/8 inches, published by Thomas McLean, London. The Collection of The Old Print Shop, New York, NY. Right: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), Indian Encampment. Oil on paper laid down on board, 7 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches, signed lower right. The Collection of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

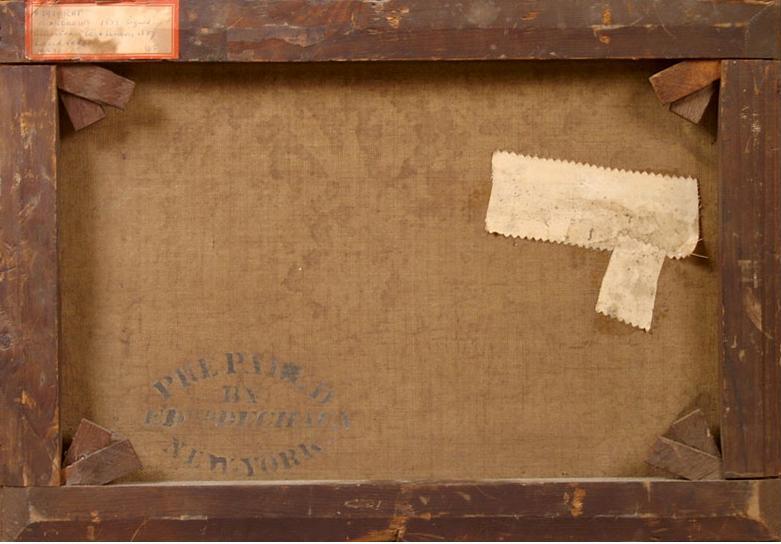

Fig. 2 One way to determine if you have a print or painting is by looking at the back. This example shows what an aged, nineteenth-century canvas and stretcher (the wood support) look like. Image courtesy of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

2. How can I determine the artist who created my painting? Is it by Thomas Cole?

First, look for a signature, which can be in the form of initials, one initial, full name, first name, etc. If you find one and can identify it, then you can assume that the work was painted by the artist. Signatures can be tested for authenticity under a blacklight; if the signature fluoresces, it could be a sign of in-paint, or an addition the original artist did not make.

Many unsigned paintings can be authentic, so if you feel that a painting has the stylistic hallmarks of an artist then you should show it to a gallery. For instance, Thomas Cole did not always sign his works. However, he is known for visible brushwork and sublime features in his landscapes including broken tree branches, rocky outcroppings, and dramatic atmospheres; moreover, his developed skies have dimension and are not flat. He painted in a naturalistic style, so the pictured scenes tend to look life-like. These types of hallmarks can be used to determine whether a work of art is by Cole. You can learn more about artists’ stylistic trademarks by viewing their works in museums, looking in books, or online.

Fig. 3 An example of Thomas Cole’s well-developed skies. Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Lake Mohonk (detail), ca. 1846. Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 30 1/8 inches. The Collection of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

Fig. 3 An example of Thomas Cole’s well-developed skies. Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Lake Mohonk (detail), ca. 1846. Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 30 1/8 inches. The Collection of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

Fig. 4 Cole was known for his dramatic portrayals of nature’s darker moments. Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Imaginary Landscape with Towering Outcrop, ca. 1846–1847. Oil on canvas, 18 ½ x 15 inches. Private Collection.

3. I would like to learn more about the artist who made my painting. What resources can I use?

A good place to start for American artists is Peter Falk’s Who Was Who in American Art?—this book gives a brief overview of thousands of artists. If the artist is well-known, you can also find a lot of information on gallery and museum websites and in scholarly books found at the local library or museum libraries. Going to museums and seeing other examples of the artist’s work can be very helpful, too.

Things get tough if there is not a lot of information available about your artist. If books and online information are not available, then the best place to look is old newspapers. These can list exhibitions, ads, and general articles that discuss your artist. Newspapers from the nineteenth-century can be found on library database systems (such as Proquest Historical Newspapers) or as hardcopies in library or museum archives.

4. Do I need to have my painting authenticated?

Authentications are important when you have a valuable work of art, but they can be costly. Sometimes galleries and auction houses can provide unofficial authentications to give you an idea of who may have painted your work—this can help determine whether an official authentication is worth the effort. It is important to note that museums typically cannot comment on the authenticity of a work due to company policies.

Catalogue raisonné committees also exist for select painters. These committees are comprised of either one or a number of experts who catalogue and authenticate all the known works of a particular artist. Catalogue raisonné groups can charge a fee for authentications, but some are free. You should try to determine whether there is a formal authentication committee for an artist if you believe you have one of their works. There are currently catalogue raisonné committees for Ralph A. Blakelock, Frederic E. Church, Jasper F. Cropsey, Sanford R. Gifford, John F. Kensett and Thomas Moran to name a few.

5. How can I determine the value of my painting?

One way to determine the value of your work of art is to consult a gallery or dealer. You will need to find a gallery that specializes in the type of artwork you believe you have (for instance, you would not want to take a Hudson River School painting to a gallery that specializes in European art). Dealers are conversant with the market often know the up-to-date value of paintings by certain artists.

If you want to do your own research or verify that a quoted value is fair, you can turn to online sources. Artnet.com and Askart.com are just two websites that list innumerable auction records for American art. You can purchase a day or month pass on these websites to access prices paid for works at auction. Browsing the records for a particular artist will give you an idea of what his/her paintings bring. This is a good way to assess worth, but you must remember that there are determining factors not analyzed in these listings such as size, condition, and desirability of specific subject matter.

For information about appraisals and a list of appraisers, click here.

6. Speaking of subject matter—does it affect my painting’s value?

To be concise: yes! Identifiable and common subject matter often make a painting more valueable. For example: Thomas Cole is revered for being the father of the Hudson River School and the artist who made American landscape painting popular. For this reason, Cole’s depictions of the American wilderness are oftentimes more desired than his European works. This directly affects the market value of his paintings—his American paintings are usually more costly than his European works.

Fig. 5 Paintings like Landscape, Sunrise in the Clove tend to be more valuable to Thomas Cole collectors since it shows an American subject. Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Landscape, Sunrise in the Clove. Oil on canvas, 5 ½ x 8 ½ in. Thomas Cole National Historic Site

7. What makes one painting more valuable than another when it comes to Hudson River School art?

The importance of the artist is the key factor in the valuation of Hudson River School art. Artists who played a major part in popularizing landscape painting are the most sought after, as are painters with a uniquely individual style, such as Thomas Cole, Frederic E. Church, Asher B. Durand, Albert Bierstadt, Sanford R. Gifford, George Inness, John F. Kensett, Fitz Henry Lane, Martin J. Heade and Thomas Moran. The paintings of these artists are highly sought after by dealers, collectors and museums. The difference in value of two paintings by the same artist often comes down to subject matter, date, size, and condition.

8. Will art galleries be willing to assist me with my painting or should I contact a museum?

Yes—it is actually best to go to an art gallery first and, if you get a sense that the painting is important and want a second opinion, then go to a museum. It is more likely that galleries will be able to give you an idea of value as they evaluate the commercial price of paintings on a daily basis. It is of paramount importance that you find a reputable dealer, though. If you don’t, you could end up selling a $250,000 painting for $2,500. My suggestion would be to pick up an art magazine such as Antiques & Fine Art, American Art Review, Art & Antiques, ARTnews, and The Magazine Antiques, look at gallery advertisements and search for information about some of the galleries online.

9. How do I know if I’m getting a fair price when selling through an auction house? What about selling to or through a dealer?

At auction you receive the value of a painting at one specific moment in time, which is subject to the world economy and who attends the auction. If two people who want the painting are present, then you’ll get a better price; however, if they aren’t there, you won’t. The advantage is that you are presenting your work to a broad audience and getting exactly what the market thinks of the painting at that moment. One of the disadvantages is that the successful buyer has to pay the hammer price plus a buyer’s premium, which can be up to an additional 25%. You are also at a disadvantage if you are the seller—you only receive the hammer price, not the buyer’s premium. A 6–10% auction house commission is also deducted for selling the work.

If you consign to a dealer, you can set a net price and not be obligated to sell the work if that price isn’t matched or bettered. This way, you have more control over what you will receive in exchange for the painting. The only disadvantages are that you may have to wait a long time before the painting sells and give a commission to the dealer. If you want to sell to a dealer then you should check their reputation and do your own homework. You can also ask the dealer what the asking price will be for the painting if you sell it to him/her and decide if you think the profit margin is fair.

10. How can I determine who owned my painting before me? Is this information important?

Sometimes the previous ownership of a painting can’t be determined, but sometimes it can. The simplest way to start is to ask the person who sold the work to you for its provenance, or history of ownership. You can also check auction records to see if the painting was ever sold at auction.

Provenance can be an indication of quality and, therefore, increase value. For example, the value of a work can be enhanced if noted collectors and/or museums previously owned it. This is due to the collectors’ or institutions’ reputation as connoisseurs, which projects a high degree of quality onto the painting.

While it is good to know a work’s provenance, it should be noted that many masterpieces and paintings of great value come with incomplete or limited information. For this reason, collectors should consider this factor, but not allow the lack of recorded history to dissuade them from acquiring a painting of remarkable visual impact and quality.

11. How can I tell if my painting is in need of restoration?

This is a hard question because it involves an individual’s own judgment. Many nineteenth-century paintings can improve with restoration. If you remove the painting from its frame and the edges under the frame are a different color, then that’s a sign that there is varnish discoloring or dirt. If you like a painting, then you should show it to a reputable restorer who can do tests to see if it can be cleaned.

One thing to note is that it is not always necessary to restore a work and, in fact, many museums and dealers prefer that a painting not be altered before viewing it. Also, if you feel it is necessary to obtain an opinion from a restorer, you should seek out the best. One way to determine if a restorer is reputable is to ask who they work with—if their clients include museums and prominent dealers, then this is a good sign. You may even wish to contact one or more of their clients for a review of the restorer’s working methods. Whatever you do, don’t be afraid to ask questions about a restorer’s techniques and why they think it is necessary to clean your painting. Never forget that you can also always get a second opinion!

Fig. 6 A before and after view of a restored Hudson River School painting. William Trost Richards (1833–1905), Coastal Scene. Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 x 48 1/8 inches, signed and dated (indistinctly) lower left. The Collection of Questroyal Fine Art, New York, NY.

Louis M. Salerno is the owner of Questroyal Fine Art in Manhattan. Questroyal Fine Art specializes in important nineteenth- and twentieth-century American paintings including works from the Hudson River School, Tonalist, Impressionist, and Modernist movements. Louis has been an avid American art collector and dealer for more than twenty years. The gallery can be reached at 212-744-3586 or via email at gallery@questroyalfineart.com.