Welcome to the Thomas Cole National Historic Site – the home and studios where the artist and early environmentalist Thomas Cole (1801-1848) lived and worked from 1836 until his death in 1848.

Thomas advocated for the preservation of the landscape through his art and writing, and his iconic landscape paintings inspired the first major art movement of the United States, now known as the Hudson River School.

Use this guide as a resource to explore the many spaces on site.

This web version of the Guide Book will lead you through the site, space by space. Start scrolling to experience the Thomas Cole National Historic Site.

A printed copy of the Guide Book is available in our gift shop and online, here.

Objects to Touch, Chairs for Sitting

You will see both historic objects and reproduction items. While the historic objects should not be touched, the reproduction items can be! Look for green dots – these are items we encourage you to touch. Please handle only the items with green dots, for even the slightest oils from our hands will harm historic objects.

Enjoy your visit!

– NEXT –

Scroll down for a quick overview of the Site’s rotating exhibitions.

![]()

EXHIBITIONS

Inside the New Studio:

Each year the Thomas Cole National Historic Site invites a guest curator to bring a new perspective to Thomas Cole’s work by creating a new exhibition in Thomas Cole’s reconstructed New Studio. The exhibitions bring together artwork from museums and private collections across the country.

OPEN HOUSE: Contemporary Art in Conversation with Cole:

An annual series of curated contemporary artist installations located within, and in response to, the historic home and studios of artist Thomas Cole.

Mind Upon Nature: Thomas Cole’s Creative Process:

An exhibition in the Main House featuring original Thomas Cole paintings, sketches, and artifacts.

– FIRST STOP –

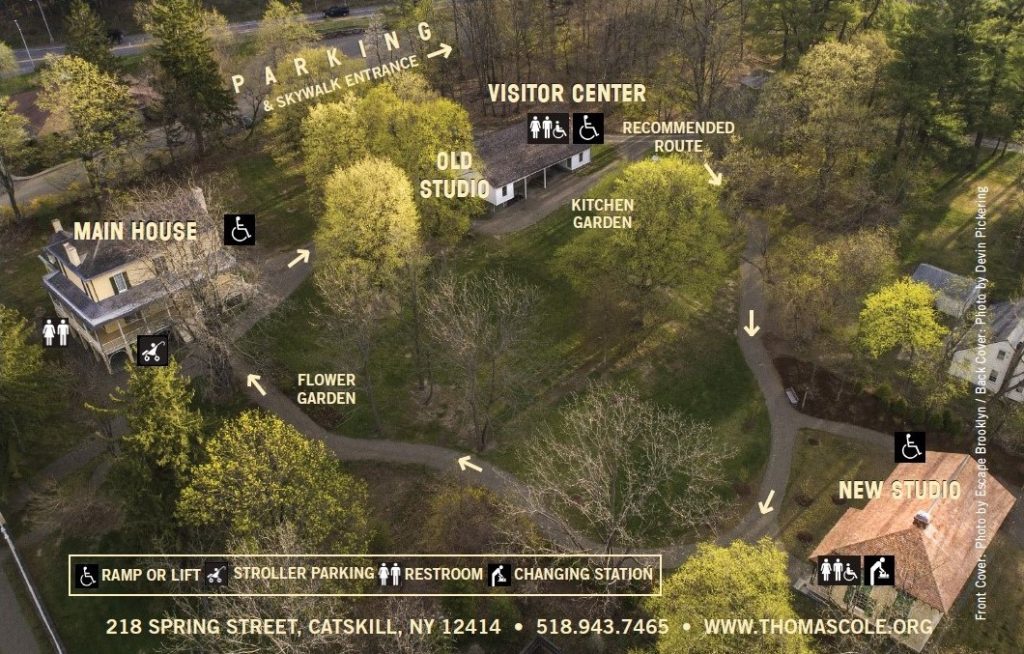

Exit the Visitor Center and take the path on your right to the New Studio. Or, you may visit spaces in any order you wish!

![]()

NEW STUDIO

The family of Maria Bartow (1813-1884), who married Thomas Cole, owned the majority of the property that now bears the artists name. From them, Thomas purchased the plot of land for this building and designed what he called his “New Studio.” It was built in 1846 and Thomas worked there until his death in 1848. The original building was torn down in 1973 before the site became a museum. We reconstructed it in 2015 with a state of the art museum gallery inside.

The family of Maria Bartow (1813-1884), who married Thomas Cole, owned the majority of the property that now bears the artists name. From them, Thomas purchased the plot of land for this building and designed what he called his “New Studio.” It was built in 1846 and Thomas worked there until his death in 1848. The original building was torn down in 1973 before the site became a museum. We reconstructed it in 2015 with a state of the art museum gallery inside.

When Thomas died suddenly at the age of 47, he left behind a studio filled with artwork and boundless unfulfilled potential. Maria preserved the space as he left it and welcomed other artists to visit. In this way, his art and ideas continued to inspire and influence the next generation of artists and the evolution of art in the United States.

Emily Cole

Emily Cole (1843-1913) was a professional artist and one of Maria and Thomas’s children. Emily used this space as her own studio and exhibition gallery. She was just five years old when her father passed away and grew to share her father’s focus on nature in her artistic practice. When you enter the Main House, look for her painted porcelains and watercolors. Emily lived here her whole life and made a living selling her art.

– NEXT STOP –

Exit the New Studio to explore the Grounds.

![]()

GROUNDS & PROPERTY

The Thomas Cole National Historic Site is on the ancestral lands of the Mohawk and other Haudenosaunee peoples, and the Mohican, Lenape, and other Algonquian-speaking peoples. It was taken from them by a series of treaties and forced displacements in the seventeenth through eighteenth centuries.

A family by the name of Thomson bought property here in 1787. Three Thomson siblings (Thomas, John A., and Catherine) began the establishment of a homestead by 1814. In the years that followed, many people have nurtured this land. During Thomas Cole’s residency, (1836-48), the property consisted of 110 acres. A salaried farmer, domestic laborers, and gardeners tended and maintained the plants and animals, and protected the property and structures. Saleable crops were grown (hay, oats, corn, and barley), and a variety of livestock were kept (horses, pigs, goats, oxen, beef cattle and chickens). The main source of income was fruit from the orchards.

If you’d like, borrow a sketchbook from stations around the site and take inspiration from nature just like Thomas Cole, Emily Cole, and many other visitors have done.

Honey Locust Tree

The large tree with sharp thorns in front of the Main House was planted in 1817, even before Thomas Cole came to live and work here. When you enter the house, look for a small painting that shows this same tree.

Greening

As we work to restore and maintain the grounds of this historic site, we are guided by principles of supporting biodiversity, reducing the use of toxic materials, and connecting people to the natural world.

– NEXT STOP –

Head to the Main House (yellow, with large porch).

![]()

MAIN HOUSE

The Main House was constructed in 1815 by a group that very likely included enslaved laborers. The 1817 census includes two enslaved persons and two free Black persons as part of the household. The Thomsons enslaved people from at least 1790 until through at least 1818.

Thomas Cole moved into this house after he married into the Thomson family in 1836. During his time here, the number of residents at the property ranged from 11-14, and this included a free Black woman recorded on the 1840 census. This household of people acted as a support system to Thomas, enabling him to produce his artwork and support the household with his earnings.

After John A. Thomson passed away in 1846, ownership of the property passed to Emily Bartow (1804-1881). As a woman, she was only able to own property because she was not married. Thomas Cole never owned the house himself.

Who Was Living Here During Thomas Cole’s Residency?

Maria Bartow Cole, Harriet Bartow, Emily C. Bartow, Frances E. Bartow, Frederic Church, Thomas Cole, Theodore A. Cole, Mary B. Cole, Emily Cole, Elizabeth Cole, Sarah Cole, Egbert, David E., Martin, Mary, Benjamin McConkey, Peter, John A. Thomson, Charlotte Thomson, free Black woman recorded (without a name) on the 1840 census (age 55-99), Jonny W., and Mr. Whitbeck.

– NEXT STOP –

Walk onto the Porch of the Main House.

![]()

PORCH

Thomas moved to America with his family in 1818 at age seventeen. He grew up in northern England – then the biggest hub for industrialization in the world. There, he saw firsthand how factories and smokestacks took over the countryside of his hometown. In the 1830s, he was alarmed to see a similar transformation taking place here in Catskill.

Thomas first came to this area by traveling up the Hudson River in 1825. He returned often and later made his permanent home here in 1836, upon his marriage to Maria Bartow (niece to the Thomsons).

This view of the mountains is one that Thomas painted many times, but this landscape was changing rapidly. A large hotel – the Catskill Mountain House – opened in 1824, drawing crowds of tourists. By 1836, there were over sixty mills, factories, foundries, and leather tanneries stretching west into the mountains. An early railroad crossed through in the 1830s, and hillsides were being clear-cut for the tanning industry.

Inside the house, you will discover Thomas’s thoughts on industrial changes to the land.

Differing Perspectives on Land

The copper-hearted barbarians are cutting all the trees down in the beautiful valley on which I have looked so often with a loving eye.

(Thomas Cole to Luman Reed, March 6, 1836)

With these immense avenues for trade […] the town of Catskill is destined to increase in wealth and population with great rapidity.

(Catskill Association formed for the Purpose of Improving the Town of Catskill, 1837)

– NEXT –

Enter the House through the front door.

![]()

ENTRY HALL

Maria Bartow (1813-1884) lived here with her sisters, cousin, uncle, and hired laborers. They came to know Thomas Cole when he first rented their small cottage (no longer standing) as a studio space. Maria married Thomas in 1836, at which time he moved in. Together the couple had five children and shared this home with Maria’s family and household staff. Check out the 1840 federal census showing a household of 11 people, reproduced nearby.

When Thomas moved in he began to redesign the interiors. He painted decorative borders onto the walls in several rooms, and selected colors, textiles, and finishes throughout the first floor, many of which have been recently restored or recreated.

Floor Cloth

This floor covering is a piece of cotton canvas that has been hand-painted and coated with layers of varnish. It was a popular feature in the nineteenth century because it was inexpensive and easy to clean. The example here is a recreation of an historic design. Thomas grew up working in the decorative arts and at one time painted floor cloths for his father’s business.

Don’t Miss the Top Hat

Thomas wore a top hat because he wanted to present himself as part of the upper class, but always struggled with bringing in enough revenue to support the household.

– NEXT STOP –

Enter the green parlor to hear from Thomas about his experience of living in Catskill, his ambitions, and his sentiments.

![]()

EAST PARLOR

Thomas wrote essays, poems, letters, and kept journals. Fortunately, many of them survive. Ask a staff member to show you the presentation, created using Thomas’s writings and paintings. We invite you to take a seat and listen as he tells his story.

Read the Audio Transcription

“Wild?”

Thomas often described scenery in the area as “wild.” Though, indigenous people had inhabited this area for thousands of years, and many were still present along the east coast in the early nineteenth century. By depicting American landscapes as uninhabited, or showing solitary indigenous figures, Thomas Cole and other painters and writers contributed to the creation of fictions about American land: that indigenous people were either never here, or if they were, they had departed long ago. These myths became legend, and served to reinforce the government’s intended erasure of indigenous culture, and the histories of the land.

Paintings

All of the paintings on the first floor are reproductions, carefully selected based on what was here in Thomas’s time, and for what they tell us about his vision. You will see original paintings on the second floor.

Don’t Miss the Chair

The upholstered chair with bookstand and candle holder belonged to Maria’s uncle, John A. Thomson. He initiated the building of the house with his brother in 1814, and lived here with many relatives and laborers until his death.

– NEXT STOP –

Exit this room and turn right into the red room down the hall.

![]()

LIBRARY

In Thomas’s time, a library was a space dedicated to expanding the mind, and likely featured art as well as books. Red-and-black Pompeiian designs and color schemes were associated in the 1830s with the display of art, suggesting that this room served as Cole’s art gallery.

The Latest Style

The wall color and border design that Thomas chose for this room were likely inspired by his trip to the ancient ruins of Pompeii, and from seeing fashionable Pompeian-inspired rooms, and the artist J.M.W. Turner’s red-walled gallery during his trip to London.

Don’t Miss the Painted Border

Near the ceiling is the exposed border that Thomas hand-painted nearly two hundred years ago. These original paintings (as well as others on this floor) were hidden beneath many layers of modern paint before they were discovered in 2014 by a paint analyst.

– NEXT STOP –

Exit this room and turn into the parlor to your right to experience some of the challenges, ideas, and relationships in Thomas’s career.

![]()

WEST PARLOR

In this room, Thomas and the family visited with patrons, friends, and fellow artists. It was a space full of conversation, where the business of art was conducted, and where Thomas expressed his opinions about what landscape art should be.

On tabletops around the room you will find four different stories told through letters. These conversations about art and business raise questions that we still grapple with today.

Team Effort

Thomas benefitted from having a large extended family that provided support for his growing artistic career. Maria’s sister Harriet is known to have shown Thomas’s paintings to visitors, and Maria was a savvy advisor on Thomas’s negotiations with potential buyers.

Don’t Miss the Wall Paint

The wall paint in this room has been made and applied through historically accurate methods. The paint was hand-mixed with oil from natural pigments, and then applied using a brush. The color, here and in other rooms, is true to the time of Thomas’s residency.

– NEXT STOP –

Head upstairs to explore the family’s more private rooms of the house. Once upstairs, follow the railing to the Bedroom.

![]()

MARIA & THOMAS’S BEDROOM

Maria and Thomas frequently exchanged letters while he travelled. Thomas’s career required that he have a presence in both New York City and Europe, but he missed his family terribly. Explore the room to find these letters.

Don’t Miss the Trunk

Thomas’s Trunk accompanied him on his two European trips, carrying everything he might need, from clothes, to sketchbooks to canvases. The trunk was not custom made but purchased at a store in New York. His initials were necessary because Thomas was not traveling in a private carriage and had to be able to identify his trunk among strangers.

– NEXT STOP –

Exit the bedroom and turn into the room on your left.

![]()

MIND UPON NATURE: THOMAS COLE’S CREATIVE PROCESS

Here, we encourage you to explore the artist’s working process and ideas. You will find an array of sketches and paintings, the books and objects that inspired him, and the pigments and materials he used to create his paintings. This exhibition is refreshed annually and highlights original objects and artwork from the museum collection and major works on long-term loan.

The Bartow Sisters

Maria’s sisters once shared this space as a bedroom. Her eldest sister Emily was the head of the house after her uncle passed away. Harriet was a teacher, and the flower garden outside was generally referred to in letters as hers. The youngest sister, Frances, spent time in the Hartford Retreat for the Insane, then known as the first hospital in the United States to employ “moral treatment” for individuals with mental illnesses. Frances was identified as “insane” on the 1870 census. No personal records of hers have yet been found.

– NEXT STOP –

Enter the Sitting Room across the hall.

![]()

SITTING ROOM

Thomas was troubled by the political climate of the United States, which he suspected was headed toward a major internal conflict. The Jacksonian Era of his time was marked by an authoritarian president, a large number of political parties, expansion westward, reform movements, debates about slavery, and the Trail of Tears.

Thomas wanted to make art that mattered and made people think. He had high aspirations about the power of art, and complained that people wanted “things, not thoughts.” In the 1840s he drafted “Lecture on Art,” in which he articulates his thoughts about how art could help to create an improved world.

As you explore the newspaper clippings, letters, and essays on the table and desk, you will hear from Thomas about his ambitions and the political climate of his era.

Major Events Happening in Thomas’s Lifetime.

Read the Audio Transcription

Sarah Cole

Sarah Cole was a professional artist known as one of the first female printmakers in the country. In this room are two of her paintings depicting the English countryside. Sarah also counseled her brother, Thomas, during moments of doubt.

Wallpaper & Carpet

The wallpaper and carpet are historic designs recreated for this space.

– NEXT STOP –

Head into the adjoining room. Ask a staff member to play the presentation.

![]()

HOUSE STUDIO

This room was Thomas’s first studio upon his marriage to Maria. Maria was often with him, reading to him while he painted and offering advice. Thomas once wrote to her, “But how can I paint without you with me to praise or to criticize?” In her journal, Maria recorded: “a volume of Scot in my hand to read to T. who was painting the Sky of his Compagna Scene.” (April 6, 1843).

We believe it was here that Thomas painted View of Schroon Mountain, Essex County, New York, After a Storm. Ask a staff member to play the presentation. We invite you to dive into Thomas’s creative process by joining him on his journey into the Adirondack mountains.

The Children’s Room

After Maria and Thomas had their first child, this room became the children’s bedroom. The couple had five children. Theodore was the eldest, and would go on to become property manager at Olana, Frederic Church’s home across the river. Mary and Emily lived the remainder of their lives here. Emily was fascinated by nature, and like her father was a professional artist. Elizabeth lived for only two days. Thomas Cole, Jr. was born shortly after his father died in 1848. He became a reverend in nearby Saugerties.

– NEXT STOP –

Scroll down to dive deeper into View of Schroon Mountain.

![]()

Creating A View of Schroon Mountain

Thomas placed several indigenous figures (two in the foreground, and several in the distance), into this painting – a departure from his more common inclusion of solitary figures.

In July of 1837 the Coles travelled to Schroon Lake in the Adirondacks. On their way they stopped in Albany to see the artist George Catlin and his “Indian Gallery” – a touring exhibition of hundreds of paintings depicting figures and customs of indigenous people, whose aggressive removal was legally sanctioned by President Jackson’s “Indian Removal Act” of 1830.

The following year, when Thomas finished this painting, one of the culminating events of the Indian Removal Act occurred. The U.S. government sent troops to violently evict all indigenous nations remaining east of the Mississippi River – particularly the Cherokee. They were forced on a deadly 1,200 mile walk west. Families were separated, and many died from sickness or starvation. It came to be known as the “Trail of Tears.”

Don’t Miss This

Maria and Thomas’s written recollections of their trip to the Adirondacks enabled us to retrace their steps. Check out the reproductions of those writings nearby.

Lumber Industry

Thomas described dashing through the woods and finding “mutilated trees” and “clearings.” Many trees in this area were cut down for the lumber industry, and it was because of such clearings that he was able to find this view.

– NEXT STOP –

Leave the Main House and walk back to the Visitor Center in the white barn to enter Thomas’s studio where he painted for seven years.

![]()

OLD STUDIO

It is in this studio where Thomas painted many of his major works, including The Voyage of Life, a series of four paintings that explore the stages of life. A reproduction of one of them, Childhood, is displayed on his original easel. Thomas worked here until 1846, at which time he moved into his “New Studio.”

When Thomas died of pleurisy in 1848 at age forty-seven, he left behind a young family. Maria was pregnant with their fifth child, and his children were all under the age of ten. His newly constructed studio (“New Studio”) was full of half-finished paintings. Through his mentorship and ideas, Thomas inspired generations of artists including Frederic Church, Susie Barstow, Asher B. Durand, and Sanford Gifford, who would collectively become known as the Hudson River School painters.

Narrative Landscapes

The Voyage of Life series illustrates Thomas’s wish to create paintings that combine landscape with narrative elements to convey ideas about humanity – what he termed a “higher style of landscape.”

Don’t Miss the Easel

The size of Thomas’s original easel helps put into perspective the scale at which he was working, and why he built a bigger space for himself in his New Studio.

– NEXT STOP –

Return to the Visitor Center to browse our selection of Thomas Cole-inspired items. If you’re looking for nearby walking trails, places to grab lunch in the village, or even Thomas’s burial site, we can help.

![]()

Images:

Exhibition installation, Thomas Cole’s Refrain: The Paintings of Catskill Creek, 2019, © Peter AaronOTTO

Exhibition installation, SPECTRUM, 2018, © Peter AaronOTTO

New Studio © Peter AaronOTTO

Main House, Photo by Rachel Stults

Entry Hall © Peter AaronOTTO

East Parlor © Peter AaronOTTO

Library Gallery © Peter AaronOTTO

West Parlor © Peter AaronOTTO

Bedroom © Peter AaronOTTO

Sitting Room © Peter AaronOTTO

House Studio © Peter AaronOTTO

Old Studio, Photo by Devin Pickering

Old Studio, Interior © Peter AaronOTTO