Use this guide as a resource to explore the many spaces on site.

This abbreviated web version of the Guide Book will lead you from space to space. Start scrolling to experience the Thomas Cole National Historic Site.

A printed copy of the Guide Book is available in our gift shop and online, here.

Thomas Cole lived here with his family. Through his art and writing he advocated for the preservation of the landscape. His paintings inspired a major art movement of the U.S., known as the Hudson River School.

Objects to Touch, Chairs for Sitting

You will see both historic objects and reproduction items. While the historic objects should not be touched, the reproduction items can be! Look for green dots – these are items we encourage you to touch. Please handle only the items with green dots, for even the slightest oils from our hands will harm historic objects.

Enjoy your visit!

– NEXT –

Scroll down for a quick overview of the Site’s rotating exhibitions.

![]()

2024 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS

“Native Prospects: Indigeneity and Landscape.”

This Year’s Exhibitions

– FIRST STOP –

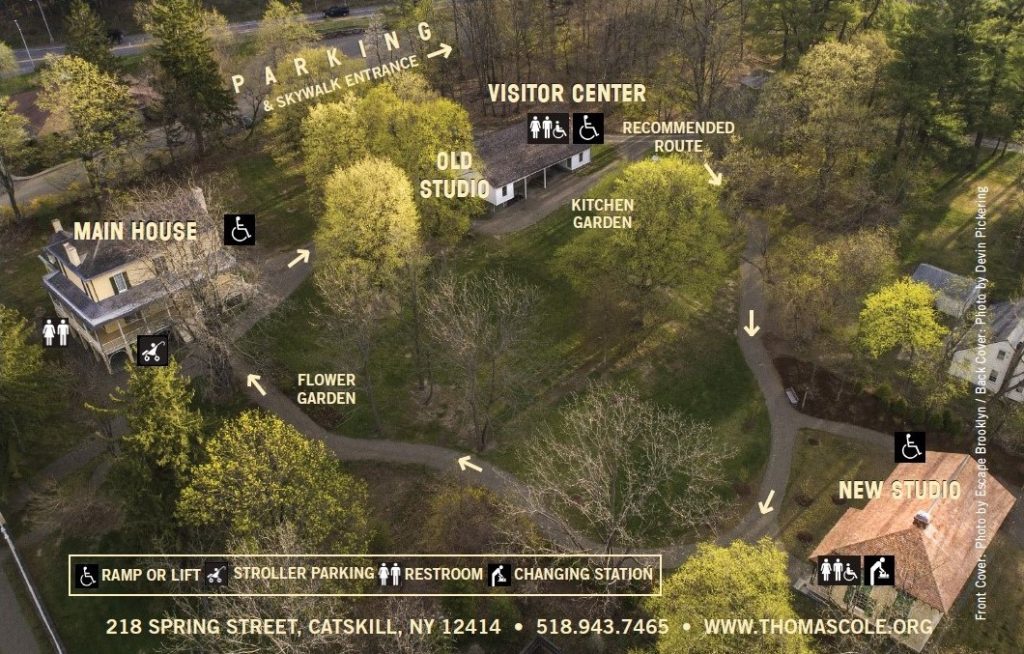

We recommend starting your visit in the 1846 New Studio to see the special exhibition, Native Prospects. Or, you may visit spaces in any order you wish!

![]()

1846 NEW STUDIO: Exhibition Gallery

The family of Maria Bartow (1813-1884), who married Thomas Cole, owned the majority of the property that now bears the artist’s name. From them, Thomas purchased the plot of land for this building and designed what he called his “New Studio.” It was built in 1846 and Thomas worked there until his death in 1848. The original building was torn down in 1973 before the site became a museum. We reconstructed it in 2015 with a state of the art museum gallery inside. Head inside to explore the exhibition.

Emily Cole

Emily Cole (1843-1913) was a professional artist and one of Maria and Thomas’s children. She used this space as a studio and gallery. When you enter the Main House, look for her painted porcelains and watercolors. Emily lived here her whole life and made a living selling her art.

About the 1846 New Studio

– NEXT STOP –

Exit the New Studio to explore the Grounds.

![]()

GROUNDS & GARDENS

The Thomas Cole National Historic Site is on the ancestral lands of the Muhheaconneok, or Mohican people, and other Algonquian-speaking peoples. The land was taken from them by a series of treaties and forced displacements in the seventeenth through eighteenth centuries.

A family by the name of Thomson bought this property here in 1787, and began the establishment of a homestead by 1814. During Thomas Cole’s residency, (1836-48), the property consisted of 110 acres. A salaried farmer, domestic laborers, and members of the family tended and maintained the plants and animals, and protected the property and structures.

Additionally, from July 20 – December 1, 2024, look for a special installation of contemporary work by Alan Michelson on view as part of the special exhibition, Alan Michelson: Prophetstown.

About the Grounds & Gardens

– NEXT STOP –

Head to the Main House.

![]()

MAIN HOUSE

The building of the Main House (1815) was financed with funds amassed from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, and may have been built in part by enslaved individuals. The Thomsons enslaved people from at least 1790 until through at least 1820.

Thomas Cole moved into this house upon his marriage into the Thomson family (1836). During his time here, the number of residents ranged from 11-14. This household of people acted as a support system to Thomas, enabling him to produce his artwork and support the household with his earnings.

After John A. Thomson passed away (1846), ownership of the property passed to Emily Bartow (1804-1881). As a woman, she was able to own property only because she was not married. Thomas Cole never owned the house.

About the Historic Household

About the Main House Enslavement History

– NEXT STOP –

Walk onto the Porch of the Main House.

![]()

PORCH

Thomas moved to America with his family in 1818 at age seventeen. He grew up in northern England – then the biggest hub for industrialization in the world. There, he saw firsthand how factories took over the countryside of his hometown. In the 1830s, he was alarmed to see a similar transformation taking place here in Catskill.

Thomas first came to this area by traveling up the Hudson River in 1825. He returned often and made his permanent home here in 1836, when he married Maria Bartow (niece to the Thomsons).

This view of the mountains is one that Thomas painted often, but the landscape was changing. By 1836, there were over sixty mills, factories, foundries, and leather tanneries stretching west into the mountains. An early railroad crossed through in the 1830s, and hillsides were being clear-cut for the tanning industry.

Inside the house, you will discover Thomas’s thoughts on industrial changes to the land.

– NEXT –

Enter the House through the front door.

![]()

HALL

Maria Bartow (1813-1884) lived here with her sisters, cousin, uncle, and hired laborers. They came to know Thomas Cole when he first rented their small cottage (no longer standing) as a studio space. Maria married Thomas in 1836, at which time he moved in. Together the couple had five children and shared this home with Maria’s family and household staff. Check out the federal census (nearby) showing a household of 11 people living here in 1840. These individuals supported Thomas’s career by relieving him of the daily tasks required to keep the property looking its best.

When Thomas moved in he began redesigning the first floor interiors. He painted decorative borders onto the walls in several rooms, and selected colors, textiles, and finishes, many of which have been recently restored or recreated.

About Maria Bartow Cole

About the Household

– NEXT STOP –

Enter the green parlor.

![]()

EAST PARLOR: The Mind of the Artist

Thomas wrote essays, poems, letters, and kept journals. Fortunately, many survive. Ask a staff member to show you the presentation created with Thomas’s writings and paintings. We invite you to take a seat and listen as he tells his story. Because his words include outdated terminology, we ask that you listen with care.

Read Thomas’s Words

“Wild?”

Thomas sometimes described scenery in the area as “wild” and its original people as “savage.” Indigenous people had inhabited this area for thousands of years, and many were still present along the east coast in the early nineteenth century. By depicting American landscapes as uninhabited, or showing solitary indigenous figures, Thomas Cole and other painters and writers contributed to the creation of fictions about American land: that indigenous people were either never here, or if they were, they had departed long ago. These myths became legend, and served to reinforce the government’s intended erasure of indigenous culture, and the histories of the land.

Don’t Miss: Red Chair with Book Stand

This chair belonged to Maria’s uncle, John A. Thomson, who initiated the building of the house with his siblings in 1814. He lived here with many relatives and laborers until his death in 1846. Documents bearing his signature reveal the names of the individuals who were enslaved by the Thomson family.

Enslavement History of this Property

– NEXT STOP –

Exit and turn right into the Library.

![]()

LIBRARY

On View This Year

As part of this year’s special exhibitions, Alan Michelson’s Shattamuc is on view in this room through December 1, 2024. The video is on a 30-minute continuous loop.

Library

Near the ceiling is the exposed border that Thomas hand-painted nearly two hundred years ago. These original paintings (as well as others on this floor) were hidden beneath many layers of modern paint before they were discovered in 2014 by a paint analyst.

In Thomas’s time, a library was a space dedicated to expanding the mind, and likely featured art as well as books. Red-and-black Pompeiian designs and color schemes were associated in the 1830s with the display of art, suggesting that this room served as Cole’s art gallery.

– NEXT STOP –

Leave the Library and walk down the stairs.

![]()

“FOOT OF THE STAIRS”

The 1846 Inventory of the house lists a cot, bed curtains, a table and a mat on the floor in this space. Someone, probably a household laborer, slept here.

The 1840 U.S. Census includes two women that were not part of the family: a free White female, age 10-14, and a free Black female, age 55-99. One of them may have slept here.

“Free, Colored Female, age 55-99” (U.S. Census, 1840)

The 1840 U.S. Census recorded a total population of 5,339 residents in the town of Catskill. Of that total, 11 were recorded as female “free colored persons” between the ages 55 and 99. One of those 11 women lived here. Was this where she slept?

About the Free Black Woman

Other laborers that may have used this space are mentioned in family letters and accounts from 1841-48: Peter (Danish), Mary (German), Martin (Scottish), Egbert, and Mr. Witbeck.

About Laborers and Residents

– NEXT STOP –

Walk up the stairs and turn left into the parlor.

![]()

WEST PARLOR: The Business of Art

Here, Thomas and the family visited with patrons, friends, and fellow artists. It was a space full of conversation, where the business of art was conducted, and where Thomas expressed his personal opinions about landscape art.

On tabletops around the room you will find four different stories told through letters. These conversations about art and business raise questions that we still grapple with today.

– NEXT STOP –

Head upstairs to explore the family’s more private rooms of the house. At the top of the stairs enter the Gallery on your left.

![]()

SECOND FLOOR GALLERY: Special Exhibitions

On view in this room you will see Mind Upon Nature: Thomas Cole’s Creative Process. Additionally, from July 20 – December 1, 2024, look for a special installation of contemporary work by Alan Michelson on view as part of the special exhibition, Alan Michelson: Prophetstown.

Original Use of the Room

Maria’s sisters shared this space as a bedroom. Her eldest sister, Emily, was head of household after their uncle died. Harriet was a teacher, and tended the flower garden outside. The youngest sister, Frances, spent time in the Hartford Retreat for the Insane, the first hospital in the United States to employ “moral treatment” for individuals with mental illnesses. No personal records of hers have yet been found.

– NEXT STOP –

Exit this room and turn right into the Bedroom.

![]()

MARIA & THOMAS’S BEDROOM

Maria and Thomas frequently exchanged letters while he travelled. Explore the room to find them, along with personal items belonging to each.

– NEXT STOP –

Enter the sitting room down the hall to the right.

![]()

SITTING ROOM: Tumultuous Times

Thomas was troubled by the political climate of the U.S., which he suspected was headed toward a major internal conflict. The Jacksonian Era of his time was marked by an authoritarian president, many political parties, expansion westward, reform movements, debates about slavery, and the Trail of Tears.

Thomas lamented that when it came to art, people wanted “things, not thoughts.” He wanted to make art that made people think critically. In the 1840s he drafted “Lecture on Art,” in which he articulates his thoughts about how art could help to create an improved world.

As you explore the newspaper clippings, letters, and essays on the table and desk, you will hear from Thomas about his ambitions and the political climate of his era.

Additionally, from July 20 – December 1, 2024, look for a special installation of contemporary work by Alan Michelson on view as part of the special exhibition, Alan Michelson: Prophetstown.

Major Events Happening in Thomas’s Lifetime

Read Thomas’s Words

Sarah Cole

Sarah Cole was a professional artist known as one of the first female printmakers in the country. In this room are two of her paintings depicting the English countryside. Sarah also counseled her brother, Thomas, during moments of doubt.

About Sarah Cole

– NEXT STOP –

Head into the adjoining room. Ask a staff member to play the presentation.

![]()

MAIN HOUSE STUDIO: Hiking with Thomas

This room was Thomas’s first studio upon moving in. Maria was often with him, reading to him while he painted and offering advice. Thomas once wrote to her, “But how can I paint without you with me to praise or to criticize?” In her journal, Maria recorded: “a volume of Scot in my hand to read to T. who was painting the Sky of his Compagna Scene.” (April 6, 1843).

It was here that Thomas painted View of Schroon Mountain, Essex County, New York, After a Storm. Ask a staff member to play the presentation. We invite you to dive into Thomas’s creative process by joining him on his journey to the Adirondack mountains. Maria and Thomas’s writings about this trip (reproductions nearby) enabled us to retrace their steps.

Read the Audio Transcription

– NEXT STOP –

Scroll down for more about this painting.

![]()

Creating A View of Schroon Mountain

Thomas placed several indigenous figures into this painting (two in the foreground, and several in the distance) – a departure from his more common inclusion of solitary figures.

In July of 1837 the Coles travelled to Schroon Lake in the Adirondacks. On their way they stopped in Albany to see the artist George Catlin and his “Indian Gallery” – a touring exhibition of hundreds of paintings depicting figures and customs of indigenous people, whose aggressive removal was legally sanctioned by President Jackson’s “Indian Removal Act” of 1830.

The following year, when Thomas finished this painting, one of the culminating events of the Indian Removal Act occurred. The U.S. government sent troops to violently evict all indigenous nations remaining east of the Mississippi River – particularly the Cherokee. They were forced on a deadly 1,200 mile walk west. Families were separated, and many died from sickness or starvation. It came to be known as the “Trail of Tears.”

– NEXT STOP –

Leave the house and walk to the white barn to enter Thomas’s studio where he painted for seven years.

![]()

STOREHOUSE

During Thomas’s residency here (1836-48), the property consisted on 110 acres of farm fields and orchards. The east half of this building was the storehouse, a crucial part of the farm operation. The family stored saleable crops such as hay, oats, corn, and barley in this building. The west half was custom-designed by Thomas to serve as his studio, where he worked for seven years.

Don’t Miss: Kitchen Garden

To honor the Indigenous history of this land, we are replanting traditional plants such as corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. Stay tuned to watch them grow!

About the Storehouse

– NEXT STOP –

Enter the Storehouse through the large green double doors to see Thomas’s 1839 studio.

STOREHOUSE STUDIO

It was here that Thomas painted many of his major works, including The Voyage of Life, a series of four paintings that explore the stages of life. A reproduction of one of them, Childhood, is displayed on his original easel. Thomas worked here from 1839 until 1846, at which time he moved into his “New Studio.”

About the Storehouse Studio

– NEXT STOP –

Return to the Shop to browse our selection of Thomas Cole-inspired items. If you’re looking for nearby walks, lunch spots in the village, or even the family burial site, we can help.

![]()

Images:

Exhibition installation, Native Prospects: Indigeneity and Landscape, 2024, © Peter AaronOTTO

New Studio © Peter AaronOTTO

Main House, Photo by Rachel Stults

Entry Hall © Peter AaronOTTO

East Parlor © Peter AaronOTTO

Exhibition Installation in Library, Alan Michelson’s Shattamuc, © Peter AaronOTTO

Foot of the Stairs, Photo by Jon Palmer

West Parlor © Peter AaronOTTO

Second Floor Gallery, 2024, Photo by Margaret DiStefano

Bedroom © Peter AaronOTTO

Sitting Room © Peter AaronOTTO

House Studio © Peter AaronOTTO

Old Studio, Photo by Devin Pickering

Old Studio, Interior © Peter AaronOTTO